The Tudor and Stuart Eras is among the most interesting period in English history, marked by sensational shifts in power, religion, and culture. Crossing from the late 15th century to the early 18th century, these two dynasties molded the course of the country, setting the stage for modern Britain. The Tudors brought steadiness after a long time of civil war, whereas the Stuarts were hooked on the challenges of administration in an increasingly complex society. This article dives into the key occasions, figures, and changes that characterized these periods, investigating the legacy they left behind.

The Rise of the Tudor Dynasty

The Tudor time started with the conclusion of the Wars of the Roses, a series of dynastic clashes that crushed Britain in the 15th century. Henry Tudor, who became Henry VII, rose triumphant at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, finishing the Plantagenet line and building up the Tudor tradition. His marriage to Elizabeth of York typically joined the warring houses of Lancaster and York, bringing much-needed peace to the domain.

Henry VII was a shrewd and cautious ruler who worked energetically to solidify his power. He fortified the government by building alliances through marriage, managing respectability with a firm hand, and reestablishing the crown’s financial health. His rule laid the establishment of a more stable and centralized government, setting the arrangement for the Tudor era’s success.

Henry VIII: The Monarch Who Changed Everything

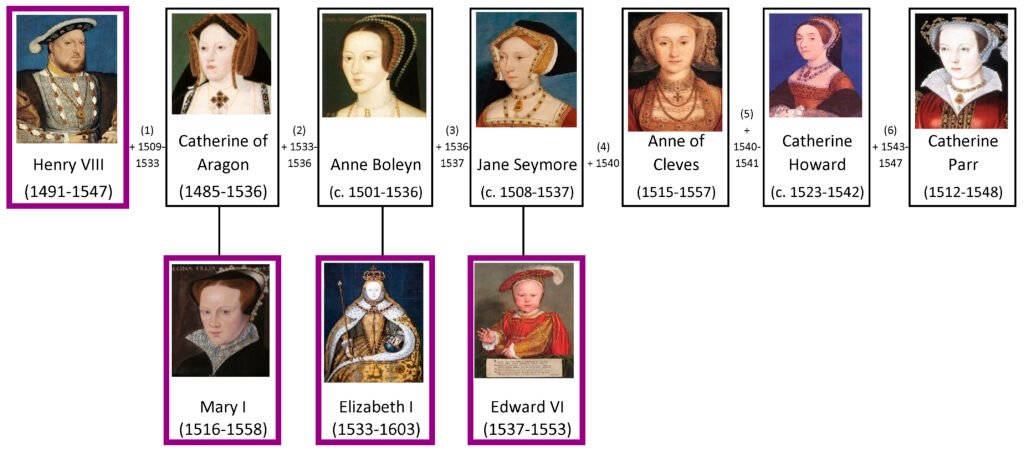

Henry VII’s child, Henry VIII, is perhaps the foremost celebrated of all English rulers. His rule was marked by noteworthy changes, most strikingly the break with the Roman Catholic Church and the foundation of the Church of Britain. Initially a devout Catholic, Henry VIII’s want for a male heir and his captivation with Anne Boleyn drove him to look for a revocation of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. When the Pope denied it, Henry took things into his own hands, leading to the English Renewal.

The Reconstruction had significant impacts on English society. The disintegration of the monasteries improved the crown and the respectability, but it also caused social and financial change. Henry’s six marriages, driven by his quest for a male inheritor, included a sensational and personal dimension to his rule. These marriages not only influenced the line of progression but also reflected the broader religious and political pressures of the time.

Edward VI and Mary I: A Tale of Two Extremes

After Henry VIII’s passing, his child Edward VI ascended the throne at the delicate age of nine. Edward’s rule, though short, was a period of strongly Protestant change. Guided by his advisors, Edward executed changes that further distanced Britain from Catholic practices, including the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer.

In stark contrast, Edward’s half-sister, Mary I, looked to return Britain to Catholicism. Her rule was marked by the mistreatment of Protestants, earning her the surname “Bloody Mary.” Mary’s marriage to Philip II of Spain was disliked, and her endeavors to reestablish Catholicism eventually fizzled, driving further religious division.

Elizabeth I: The Golden Age of the Tudor Era

Elizabeth I, the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, ascended to the position of royalty in 1558 and is frequently respected as one of England’s most noteworthy rulers. Known as the “Virgin Queen,” Elizabeth skillfully explored the religious and political challenges of her time, keeping up a sensitive adjustment between the Protestant and Catholic groups inside her domain.

One of the foremost noteworthy occasions of Elizabeth’s rule was the overcome of the Spanish Armada in 1588, which set up Britain as a major maritime control. Elizabeth’s rule too saw a social renaissance, with the prospering of English literature and drama, most strikingly the works of William Shakespeare. Her time is frequently alluded to as the Brilliant Age, a time of exploration, artistic accomplishment, and national pride.

The Stuart Dynasty Begins: James I and the Union of Crowns

The passing of Elizabeth I in 1603 marked the conclusion of the Tudor line and the start of the Stuart period. James VI of Scotland, the child of Mary, Ruler of Scots, ascended the English position of royalty as James I, joining together the crowns of Britain and Scotland. This union was more individual than political, as the two countries remained legitimately partitioned until the Acts of Union in 1707.

James I’s rule was characterized by pressures from Parliament, especially over money-related and religious issues. His conviction in the divine right of lords clashed with the developing power of Parliament, setting the stage for future clashes. The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a fizzled endeavor by Catholic plotters to kill James and blow up Parliament, highlighted the continuous devout pressures in Britain.

Charles I and the Path to Civil War

James I’s child, Charles I, acquired his father’s conviction in the divine right of rulers, but his relationship with Parliament was indeed more hunted. Charles’s endeavors to govern without Parliament and his burden of disagreeable taxes led to broad discontent. His devout approaches, which were seen as well as thoughtful to Catholicism, further distanced his subjects.

The pressure between Charles I and Parliament inevitably emitted into the English Civil War, a conflict that set the Royalists (supporters of the lord) against the Parliamentarians (driven by figures like Oliver Cromwell). The war finished with the defeat of the Royalists and the phenomenal trial and execution of Charles I in 1649, an event that stunned Europe and marked the brief annulment of the monarchy.

The Commonwealth and Protectorate: England’s Period Without a Monarch

After the execution of Charles I, Britain was announced a republic, known as the Commonwealth, with Oliver Cromwell as its driving figure. Cromwell’s rule, which afterward became a de facto fascism under the title of Lord Protector, was marked by Strict arrangements and military campaigns in Ireland and Scotland.

Life under Cromwell’s administration was stark, with a focus on devout and ethical change. Theaters were closed, Christmas celebrations were prohibited, and the impact of the Church of Britain was abridged. In spite of his endeavors, Cromwell’s government struggled to gain widespread support, and after his passing in 1658, the Commonwealth rapidly collapsed.

The Restoration of the Monarchy: Charles II and the Return of the Stuarts

The Restoration of 1660 saw the return of Charles II, the child of Charles I, to the position of royalty, marking the conclusion of the Commonwealth and the restoration of the Stuart monarchy. Charles II’s rule was a period of relative solidness and is frequently recalled for its gratification and the prospering of arts and culture, a stark difference from the strict Puritanism of the Cromwellian time.

However, Charles II’s rule was not without challenges. The Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666 were major calamities that struck during his time. In any case, Charles managed to reestablish the monarchy’s specialist, although he ruled with a cautious approach to maintain a strategic distance from the destiny of his father.

James II: The Last Stuart King

Charles II was succeeded by his brother, James II, whose straightforwardly Catholic confidence led to far-reaching doubt and resistance. James’s endeavors to advance Catholicism and his dictatorial style of governance distanced much of the English people and political elite.

The Great Revolution of 1688, a largely bloodless coup, saw James II removed and supplanted by his Protestant daughter Mary and her spouse, William of Orange. This occasion marked the conclusion of the Stuart dynasty’s direct rule and built up a constitutional government, restricting the powers of the crown and laying the establishment of modern parliamentary democracy in Britain.

Religious and Political Change During the Tudor and Stuart Eras

The Tudor and Stuart Eras were periods of critical devout and political change. The English Transformation, started by Henry VIII, led to the creation of the Church of Britain and a lasting break with Rome. This devout move had significant suggestions for English society, influencing everything from administration to daily life.

Politically, these periods saw the continuous move from absolute monarchy to a constitutional framework. The battles between the crown and Parliament, especially amid the Stuart period, highlighted the limits of royal control and set the stage for the improvement of parliamentary democracy.

Cultural and Scientific Advancements

The Tudor and Stuart Eras were also times of exceptional social and scientific progressions. The Renaissance, which had spread from Italy to Britain, brought renewed intrigue in art, literature, and exploration. Figures like William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Sir Francis Drake became synonymous with the era’s social accomplishments.

The Stuart period saw the beginnings of the Scientific Transformation, with figures like Sir Isaac Newton and Sir Francis Bacon making groundbreaking commitments to science and philosophy. These progressions laid the basis for the Edification and the advanced scientific method.

Women in the Tudor and Stuart Eras

Women’s parts during the Tudor and Stuart periods were complex and changed. Queens like Elizabeth I and Mary I wielded noteworthy power, whereas noblewomen regularly played vital parts in politics and society. However, the lives of conventional ladies were to a great extent compelled by societal expectations, with restricted access to instruction and lawful rights.

Marriage, legacy, and social status were key variables that formed women’s lives. In spite of these confinements, a few ladies managed to exert impact, whether through support, intellectual pursuits, or managing estates.

The Legacy of the Tudor and Stuart Eras

The legacy of the Tudor and Stuart periods is still felt in Britain nowadays. These periods laid the foundations for modern British government, law, and culture. The move from outright to protected government, the foundation of the Church of Britain, and the social accomplishments of the Renaissance and Scientific Transformation all have enduring impacts.

The Tudor and Stuart periods moreover played a vital part in forming British personality, with figures like Elizabeth I and Shakespeare becoming national symbols. The changes and clashes of these times helped forge a more bound together and modern Britain, setting the stage for its future as a worldwide power.

Conclusion

The Tudor and Stuart periods were times of dynastic dramatization, devout change, and significant change. From the foundation of the Tudor tradition by Henry VII to the Glorious Revolution that finished the Stuart line, these periods were marked by noteworthy events that reshaped the course of English history. The legacy of these times is reflected within the enduring institutions, social accomplishments, and national identity that proceed to characterize Britain nowadays.

FAQs

What were the key differences between the Tudor and Stuart dynasties?

The Tudors established a more centralized monarchy and initiated the English Reformation, while the Stuarts struggled with issues of royal authority and faced significant conflicts with Parliament.

How did the Reformation affect England during these periods?

The Reformation led to the establishment of the Church of England, significant religious conflict, and the eventual division between Protestant and Catholic factions within the country.

What was the significance of the English Civil War?

The English Civil War was a critical dispute brought about by the interim overthrow of the monarchy, the execution of Charles I, and the rise of a republic under Oliver Cromwell.

How did Elizabeth I manage to maintain power as a female ruler?

Elizabeth I used her intelligence, political savvy, and the image of the “Virgin Queen” to navigate religious and political challenges, maintaining a strong and stable reign.

What were the major cultural achievements of the Tudor and Stuart eras?

The Tudor and Stuart eras saw the flowering of English literature, particularly during the Renaissance, with figures like Shakespeare, and the early stages of the Scientific Revolution with thinkers like Newton.